Ripley, Ohio is a place that deeply resonated for me. My Fund For Teachers fellowship led me to this small town with a big Underground Railroad history. Here are three reasons I cannot get Ripley off my mind.

1. The Riveting Story of John P. Parker

Ripley resident John P. Parker was a man of African descent who regularly snuck into the slave state of Kentucky to help free enslaved people by bringing them across the Ohio River to the free state of Ohio. Parker conducted these nighttime rendezvous at great risk to himself and to his wife and children. For helping someone gain freedom, a Black person faced the promise of physical violence, being returned to (or sold into) slavery, or being lynched. Yet John Parker helped free between 600 and 900 people during his life in Ripley, Ohio.

Parker was an avid reader, a successful entrepreneur and an inventor (he held three patents). I cannot imagine a person of such prominence risking everything by getting into a boat, night after night, to free people he did not know.

Another story that resonated for me took place during Parker’s younger years, when he was still enslaved but deeply determined to secure his own freedom. When he was about to be sold for a third time, he convinced a white woman he knew to buy him. By this time, Parker had become a skilled metal worker. As part of their agreement, she hired him out to a foundry owner. Parker had a quota of metal castings to complete each day and his salary went the woman. But, the foundry owner paid him for each casting he produced above and beyond his daily quota. He often had himself locked in the foundry overnight and over the weekends so he could keep churning out work. Incredibly, he was able to earn the $1,800 (more than $56,000 in today’s dollars) he needed to buy himself out of slavery in just a year and a half.

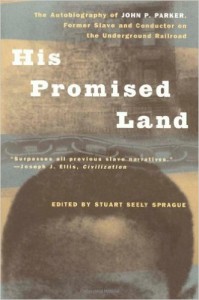

I strongly recommend his autobiography, His Promised Land, much of which reads like an action movie. The story of Parker, at eight years old, being sold and forced to walk more than 600 miles in a chained coffle from Virginia to Alabama, the multiple, creative escapes (which ended in discovery each time), and his absolute determination to learn to read and to educate himself are also inspirational.

The origin of Parker’s autobiography itself is interesting. He didn’t actually write it. Instead, his oral history was taken in the 1880s, as part of a reporter’s interest in another topic: uncovering the truth behind a portion of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin. There had been rumors that there was truth in Beecher Stowe’s chapters about the freedom-seeker “Eliza” crossing the iced over Ohio River. This reporter came to Ripley to find the true story. In his interview on the topic with Parker, the reporter convinced Parker to share the story of his life.

Sadly (although not surprisingly), Parker’s story was not published until 1996, “due to racism” as well as Parker’s “lack of celebrity and the illegibility of the manuscript,” according to the current editor, Stewart Seely Sprague. If you are looking for some exciting summer reading, regardless of your interest in history, this is the book. You can feel extra good purchasing because all proceeds go to the John P. Parker Historical Society.

2. The Puzzling Fact that Ripley’s History is Not Better Known

John Parker was not working in a vacuum. After ushering freedom-seekers across the river, he brought his charges to one of many “safe houses” in Ripley. One of the most effective was the home of Reverend John Rankin, which still stands at the top of a hill that can be seen across the Ohio River in Kentucky and is now also a museum. Rankin was another astonishing character in Ripley. You can read about him here and here.

Ripley formed one of the largest and most effective Underground Railroad “trains.” According to Dewey Scott, a local historian and docent at the John P. Parker House, a “big train” involved 10-12 houses that worked together to help enslaved people become free. Ripley’s roster of abolitionists included 329 people, a little over 10% of the population, though not everyone was hiding runaways. Mr. Scott points out that there were many ways residents helped. There were six shoemakers in town, many more than needed to protect the feet of Ripley residents. Abolitionists were secretly buying and distributing the shoes to people fleeing slavery, many of whom were about to experience their first winter. Others helped by cooking, sewing, passing messages, keeping watch, etc.

Given all of this, it is astounding to me that Ripley is not better known in the Underground Railroad story.

3. The Wonderful Example of People in Ripley Working Together Again

Just as the people of Ripley worked together in the 1800’s to fight slavery, a group of people in Ripley are working together again today – this time to make their town’s rich an important legacy of social justice better known.

As Oliver Sacks, M.D. described in Oaxaca Journal, an amateur is someone who does something out of personal passion, rather than a professional role. Sacks argues that many compelling discoveries have been made by amateurs, due to their intrinsic interest and personal drive. This is clearly evident in Ripley, as these amateur historians are discovering their local history, preserving it, and helping it come alive for others.

Part of this story starts with teacher-turned-principal Charles Nuckolls, who was born a few miles upstream on the Kentucky side of the Ohio River. Nuckolls was hired as the principal of a public school in Cincinnati named after John Parker but didn’t know who Parker was. Once he began his research, he found himself on the path to a deep investment in Ripley, John Parker, and its history. He tried to buy Parker’s home himself in an attempt to preserve it. When the owner discovered its value, and the property the price was raised beyond the means of Nuckolls. But the home was acquired with others, including attorney Robert Newman, who had obtained a copy of the original manuscript of Parker’s autobiography and like others, could not put it down.

I spoke to several people (besides Nuckolls) involved with the Society whose passion and commitment almost made me want to move to Ripley. The first was Dewey Scott, the wonderful docent of the Parker House, who made the story of Parker’s life come alive. Others include Peggy Mills Warner (another former teacher), who shared wonderful stories about the local history and book recommendations for me and my students. Likewise, Alison Gibson has turned Ripley’s public library into a key research institution with extensive primary and secondary sources about Ripley and about the Underground Railroad

Together, these people (and many others) are part of the John P. Parker Historical Society. They have succeeded in raising the funds to restore Parker’s home on the riverfront, which is now a small, top-notch museum, complete with commissioned paintings depicting the narrative of Parker’s life.

The John P. Parker Historical Society has worked to make Parker’s home recognized by the U.S. Park Service as a National Historic Landmark. In doing so, they were also able to have 300 sites and buildings in Ripley also identified as preservation-worthy.

Even better, the society is working with Sherrod Brown, a U.S. Senator from Ohio, who introduced a bill to designate the John P. Parker House as a United States National Monument. As such, the Parker home would be owned and managed by the US Park System, assuring that it would be preserved for future generations interested in looking back at one of the many unsung individuals who risked his life to fight the institutionalized racism of slavery.

***

Links to all Underground Railroad blog posts:

Leave A Response